LONDONOSTALGIA

The view of a London populated by gentleman gangsters in the East End, cockney street traders, and the Blitz spirit, appeals to gentrified urbanites looking for local colour, writes James Heartfield. First published in Blueprint September 2004

When people left the countryside to work in the towns, their attitudes to nature changed. Landscape was romanticised, viewed with nostalgic longing. Once it ceased, for most people, to be a place of work, nostalgia created a mythical 'countryside' that elbowed aside the real one.

Urbane critics like to scoff at the romance of the countryside. But there is another kind of romanticism, trendier but maybe just as bogus, and that is the romanticism of London: Londonostalgia. The chief Londonostalgics are Peter Ackroyd, author of the city's 'biography' published in 2000, and poet Iain Sinclair, whose account of circumnavigating the M25 was a surprise hit in 2002. Ackroyd's London antiquarianism was on display at the recent London Architecture Biennale, of which he was president. Both Sinclair and Ackroyd acknowledge a debt to Mother London by the prolific science -fiction writer Michael Moorcock.

Alongside the literary expressions of London pride is the growing political power of London; its mayor, and his ability to get one over on the Prime Minister; London's booming economy, and the city's monopoly over the financial, publishing and creative industries that create one sixth of the entire country's wealth.

The 'urban renaissance' celebrated by Lord Rogers of Riverside was pre-eminently a London renaissance, the emergence of 'cafe society' in Shoreditch, Islington, Fulham and Putney. Time Out's Robert Elms - Ken Livingstone's mini-me - proposed on BBC Online that 'the People's Republic of London, with the population of about eight million, would be the eighth-richest country in the world, with one of the most modern and dynamic economies' - though actually it would be only 31st richest, above Saudi Arabia but below Egypt, with a GDP of $253bn (£139bn).

Just as the cockney chest is swelling with pride, however, there are morbid signs in London's self-image emerging. Against the superficial trend towards modernity - millennium bridges and riverside apartments - the stronger undercurrent is for a gloomy nostalgia.

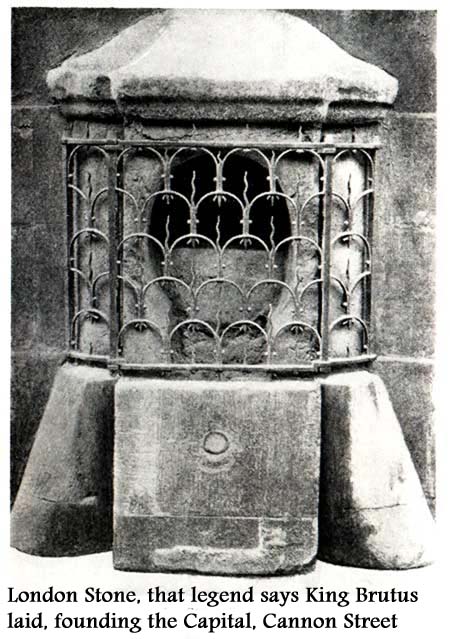

The London imagined by Ackroyd, Sinclair and Moorcock is, above all, a backward-looking one. The Londonostalgics adore everything arcane and archaic about the city. They have revived the mythical origins of King Lud, and of Brutus, coming from Troy 1,000 years before Christ. 'Those of a sceptical mind may be inclined to dismiss such narratives, but the legend of a thousand years may contain profound and particular truths,' says Ackroyd, echoing the closing lines of Moorcock's Mother London: 'By means of our myths and legends we maintain a sense of what we are worth and who we are.'

But how many Londoners had ever heard of King Lud, let alone honoured him? It was a story made up by the medieval scholar Geoffrey of Monmouth, and discounted as early as the 16th century by historian John Stow as an attempt to aggrandise the city's history by 'interlacing divine matters with human'. Ackroyd's resuscitation of the fable of King Lud is not a passing whimsy, but characteristic of his antiquarian predilections, and central to his theme of an 'underlying identity', 'the permanent and unchanging nature of London… thereby reaffirmed in the very face of change'. If it sounds too awkward of England, at least we can sing 'there'll always be a London'. It is pointed that Ackroyd's admirers, like Will Self, have baulked at the scope of his latest book, Albion: the origins of the English imagination - it is acceptable to affirm the eternal London, but eternal England is too much to swallow.

Emotionally, Ackroyd, mayor of Londonostalgia, appeals to history to underline his conservative faith in continuity. But as history, this is very poor scholarship - the subordination of historical truth to Heritage London.

Londonostalgics owe a debt to 'psychogeography' - situationist Guy Debord's 'study of the effects of the geographical environment… on the emotions and behaviour of individuals'. Stewart Home and Tom Vague perfected a punk psychogeography that soaks up the local colour, as in Vague's Notting Hill tales of Christie, Rachmanism and race riots.

The psychogeographers' method is to wander the town, without a pre-planned route, like Walter Benjamin's footsore flaneur, dwelling on the idiosyncratic and esoteric corners. According to writer Phil Baker, Ackroyd's London 'is underpinned by an ultimately irrationalistic psychogeography, claiming that the character and atmosphere of different London districts inhere over time by an echoic haunting process'. Iain Sinclair brings in another influence in the Sixties' Earth Mysteries school which revived the idea that ancient monuments are connected by ley-lines, unmarked connections across the countryside, with magical powers.

The very idea of a history of London is full of pitfalls. The mere persistence of the formal tag 'London' masks what is largely discontinuous. Settlement emanating from the same spot over two millennia disguises the fact that places played quite different roles in each era. Making 'London' the subject tempts scholars to sum up the essence of London - but these are always artificial definitions. Porter and Inwood alight on the 'multicultural' London - as if the medieval Jewish money-lenders, Hanseatic traders, and West Indian service workers were all part of the same trend. 'Multiculturalism' is, above all, a contemporary label designed to assimilate a whole range of distinct conflicts into one story of growth.

Ackroyd finds London's essence in the 'organic continuity of its financial life'. Trading London seems to be a plausible essence. But London was created as an administrative centre of the Roman Empire, where wealth came from taxes exacted on the surrounding countryside, not trade. As late as the 12th century Boston, not London, was Britain's leading port. But it is, of course, true that with the ascendance of trade London dominated mercantile Britain, though it subsequently lost out to west-coast cities like Liverpool and Bristol in the Atlantic trade, and to northern cities in the industrial revolution of the 19th century. The assertion of continuity misses out the real stuff of history - change.

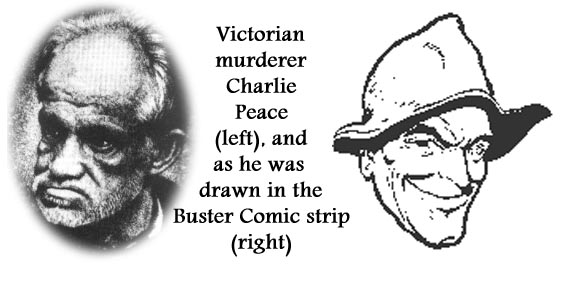

The Londonostalgics, though, are not interested in history, but myth, and the mythic London they create is perverse. It revels in the violent and sordid. Ackroyd in particular draws on all the hysterical, church-led accounts of the East End residuum to paint a terrible - read 'titillating' - picture of the mob. But where Victorian philanthropists like Mayhew exaggerated the degeneration out of a sense of fear, Ackroyd, with the advantage of distance, glories in the mob's supposedly primal energies, as he does in the London crowd and Bartholomew's Fair.

Drawn to the dark side, Ackroyd, spurred on by Iain Sinclair, revels too in the supposed history of necromancy in London. Preoccupied with the marginal figure of Elizabethan magician John Dee, divining ancient runes in the pompous churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor, even drawing imaginary ley-lines between them, and all over London, Ackroyd insists that 'the city itself remains magical; it is a mysterious, chaotic and irrational place which can only be organised by means of private ritual or public superstition'.

A weirder theme is the recurring fantasy of 'a forgotten troglodytic race' that in Michael Moorcock's version 'had gone underground at the time of the Great Fire' - a fantasy that also appeals to Ackroyd. He is drawn to the 'mysterious' world of London's sewers, where 'the figure of the underground man is so potent'.

Joseph Bazalgette's 1868 sewers were a triumph of rationalism - substituting brick-lined tunnels as carriers of waste for the Thames and its tributaries. But they are turned instead into the setting for a Gothic horror story. This is what the French call nostalgie de la boue, or Beckett's 'sniffing the turds of history'. Today, ghettoes are once again identified with sewers, except that what repelled the Victorians attracts the Londonostalgics.

These themes of the mob, the occult and the underground, are central to the nostalgic idea of London. It is worth asking why they are in vogue.

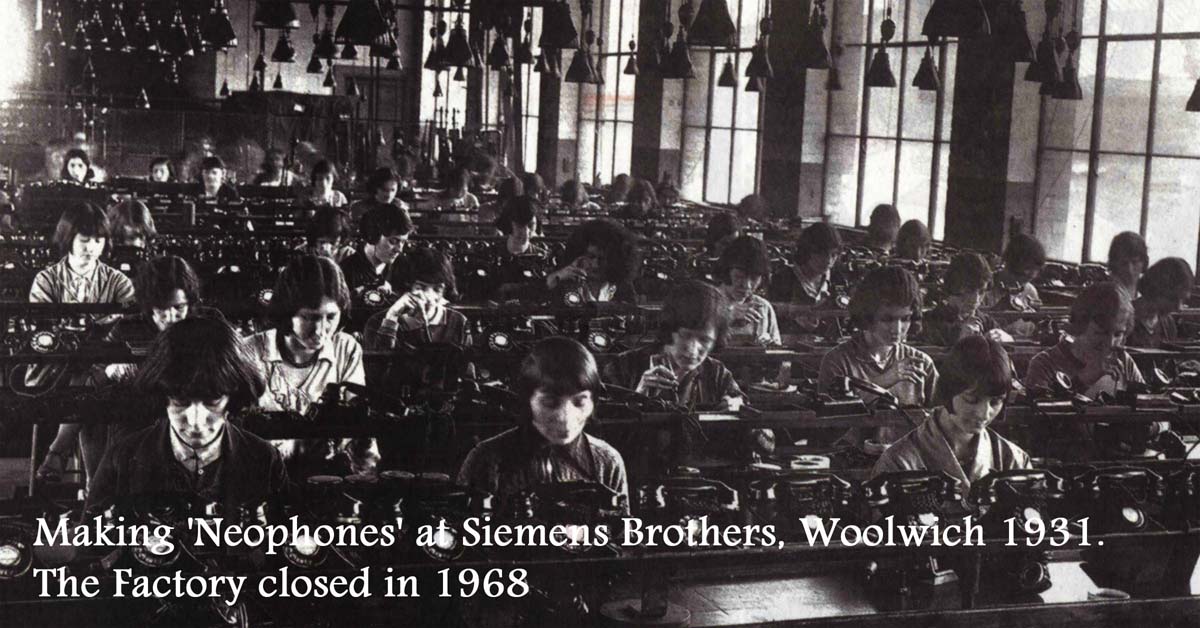

Behind the attraction is the passing of a way of life. Though 'eternal London' is an appeal against change, it is also nostalgia for what has already passed away. The London yearned for is a mythical one of gentleman gangsters in the East End, cockney street traders, the mingling of high and low in the Elizabethan crowd and the spirit of the Blitz. What real activity is imaginatively reinvented as occult ritual hidden from view undertaken by an ancient, underground race? It is the world of work. London's manual work is passing away - from the silk weavers of early 19th-century Spitalfields, to the Bryant and May matchgirls (whose poisonous factory has been turned into the fashionable Bow Quarter apartments) to the 10,000 jobs at the Beckton Gas and Light Works in 1900, the 27,000 registered Port of London workers in 1947 reduced to a fraction and relocated to Tilbury and Southampton by 1967, and the 30,000 workers at Ford's Dagenham plant, now closed.

These form the race of 'troglodytes' that haunts London. They have been cleared away in the transformation of London into a city dedicated primarily to business services (844,500 workers) and retail (500,000) compared with just 250,000 remaining manufacturing workers, concentrated mostly in the Lea Valley or Park Royal. 'There's a lot to be said for poignant dereliction,' wrote Hugh Pearman in the Sunday Times on 30 May, regretting the redevelopment of Paddington. 'I love it: the old, now silent factories, the rusting railway sidings, the buddleia sprouting from the walls and the birches shouldering through the pavements.' But this is poignant in the same way Roman ruins are - the sentimental pleasure of reflecting on the downfall of a once-mighty race.

The changing employment structure corresponds to a changing sociology. Where the early Eighties saw a flight out of the impoverished inner cities to the suburbs, the Nineties saw a reverse movement, the gentrification of inner London that Lord Rogers celebrated as a renaissance. The vacated shells of industrial London were turned into expensive apartments and art galleries. With rising house prices it was working-class London that was being driven to the suburbs.

The Londonostalgics pour scorn on the new Londoners, who, says Joseph Kiss in Moorcock's Mother London, come 'from the Home Counties… They're driving out most Londoners and taking over our houses, street by street… I know people born in Bow who've had to move as far as Stevenage to find a house they could afford. And who's getting the house in Bethnal Green, my boy?'

Sinclair, in London Orbital, agrees: 'Waltham Abbey and the inhabitable pockets of Epping Forest were white Cockney on the drift, the tectonic plate theory. Hackney becomes Chingford, Notting Hill relocates to Hoxton. Cabbies, always awkward sods, had uprooted years ago: try finding one now who did not grow up in Bethnal Green and who doesn't now live in Hertfordshire or Essex.' It is the new, gentrified Londoners who are the natural audience for Londonostalgia. Blue-plaque London is a cornucopia for the heritage merchants. Ackroyd is writing copy for tour guides, and signage for the London Dungeon. Shoreditch's Victoriana makes it an attractive venue for graphic designers who hope the lingering historical stench will lend their studios a bit of local colour.

Who else are these tales of cheeky cockneys written for, if not the mockneys that have taken their place? But let's not join in the nostalgia. Cockney is not better than mockney. 'Cockney' is an insult, from a 'cock's egg', meaning something queer, then an effeminate man, until it was stuck on to the people of the East End. Historian Gareth Stedman Jones explains in his work Metropolis that the cockney has always been a caricature, and a vicious one at that.

The psychogeographers chose to wander without a destination, letting the geography impact on the psyche, as thoughts run unbidden; street wise but world foolish. But wandering without purpose is the privilege of a leisure class. Sinclair, Ackroyd and Vague are just churning out fat, obscure books that meander through time and space to fill up the yawning leisure time of the new Londoners. Londonostalgia is the imaginary reappropriation of a disparate history.

Most importantly, Londonostalgia is only possible because 'London' is over - notwithstanding its claims to eternity. There really is no recognisable unit called London that can be parcelled together under one name any more. The green belt cannot contain the sprawling suburbs.

Like all cities, London owes its origins to that first division of labour between town and country, but with intensive farming, more and more land is becoming available as London expands outwards. But as it expands, it ceases to be anything like London. Rather, the growth is the growth of the South East, spurred on by the shift from Atlantic to European trade. London has dissolved as its boundaries expand and become more porous.

For more than a century, the London of the Londonostalgics has been a fraction of the administrative London. Victorian London outnumbers medieval London by more than 6:1. Since 1965, Greater London has incorporated Essex boroughs like Walthamstow, and other 'railway suburbs'.

The Londonostalgics jeer at the suburbs - 'Barratt hutches', 'kennels', 'Lego homes'. 'They come in kits,' says Sinclair. But for all that bitter condescension, London's suburbs are where most of its population now lives. Put another way, they do not live in London at all, but Stevenage, Shepperton or even Oxford and Brighton, commuting sometimes to work or play in the central heritage zone

Some Londonostalgic texts

Peter Ackroyd: London: The Biography (2000), Hawksmoor (1985), Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem (1994)

Iain Sinclair: London Orbital (2002), Lights Out for the Territory (1997), Lud Heat (1975), Downriver (1991)

Michael Moorcock: Mother London (1988)

Tom Vague: Notting Hill Steven Inwood: A History of London (1998)

Roy Porter: London: A Social History (1994)

Liza Picardie: Restoration London (1997)

Maureen Waller: London 1945 (2004)

Gilda O'Neill: My East End - Memories of Life in Cockney London (1999)

Stephen Smith: Underground London (2004)